+44 1349 470002

United Kingdom

+44 1349 470002

Cart

Enquire

Enquire

ITIL® Practitioner

ITIL® Practitioner

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Transition

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Transition

ITIL® Service Capability - Operational Support And Analysis

ITIL® Service Capability - Operational Support And Analysis

ITIL® Service Capability - Planning, Protection, And Optimization

ITIL® Service Capability - Planning, Protection, And Optimization

ITIL® Service Capability - Release, Control & Validation

ITIL® Service Capability - Release, Control & Validation

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Strategy

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Strategy

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Operation

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Operation

ITIL® Service Capability - Service Offerings & Agreements

ITIL® Service Capability - Service Offerings & Agreements

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Design

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Service Design

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Managing Across The Lifecycle

ITIL® Service Lifecycle - Managing Across The Lifecycle

Certified EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Foundation

Certified EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Foundation

Certified EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Foundation and Practitioner

Certified EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Foundation and Practitioner

Certified EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Practitioner

Certified EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Practitioner

Certified Data Protection Officer (CDPO)

Certified Data Protection Officer (CDPO)

Dealing with Subject Access Requests (SAR)

Dealing with Subject Access Requests (SAR)

Dealing with Subject Access Requests (SAR) - An Executive Briefing

Dealing with Subject Access Requests (SAR) - An Executive Briefing

EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Awareness

EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) Awareness

Programming & Database

Programming & Database

“Too much change is really too little change resource for delivering what is required…quite simply, the demand for change exceeds the available resource – the change capacity

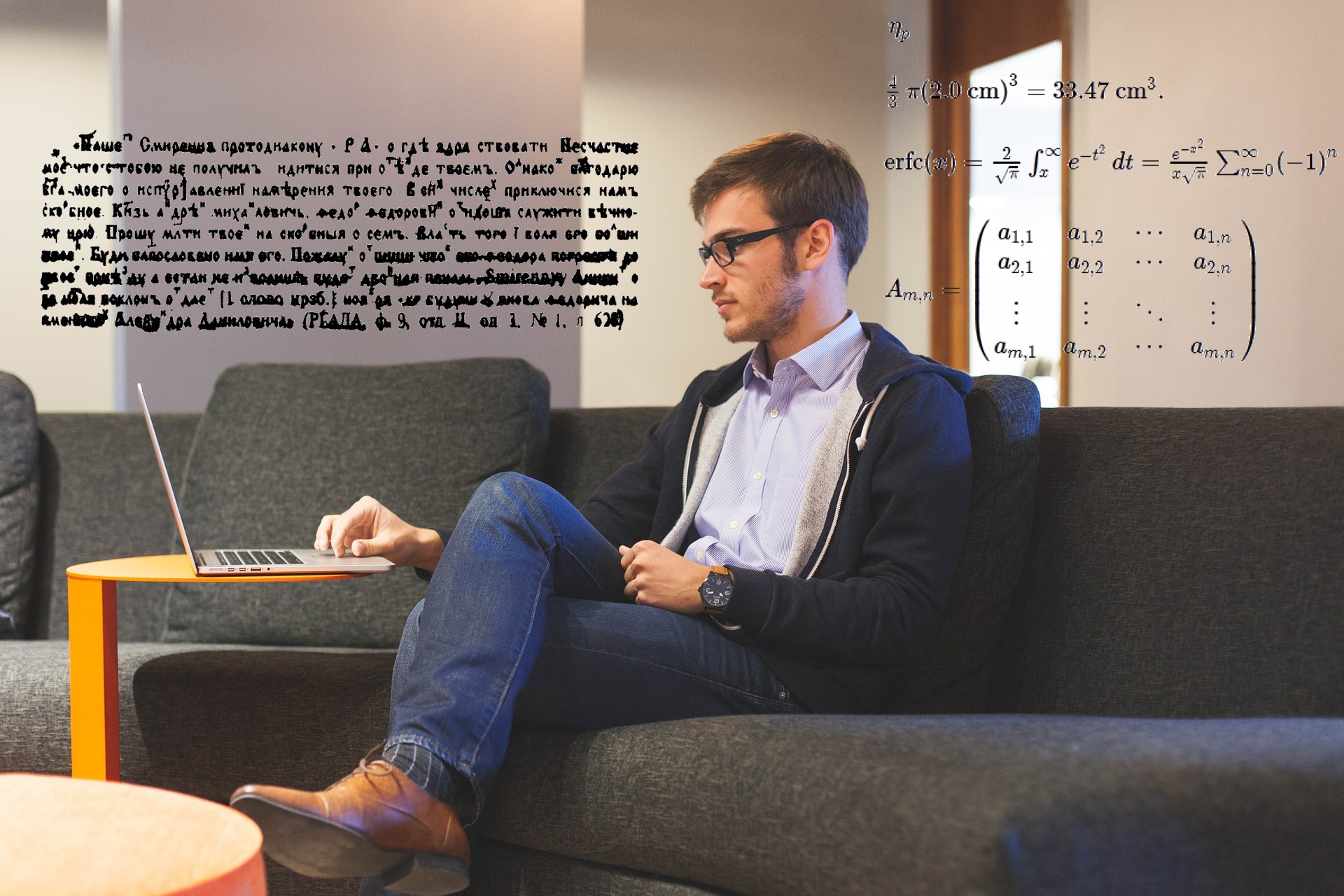

Exploring the problem of too much change and what to do about it

Adrian Boorman: “Hello, and welcome to this video brought to you by Pearce Mayfield.

You don’t need me tell you that we live in a Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous world – certainly not always a comfortable place to be, especially for change resistant old dinosaurs like me! It’s this problem of too much change that is becoming a hot topic amongst many organisations with even quite small businesses and teams facing a deluge, maybe even a tsunami, of change. Recent research by Prosci, the US based Change Management consultants, has shown that not only are 77% of their respondents already near or even above change saturation; but that this figure goes on increasing every time they carry out their bi-annual survey.

With me in the studio today, to discuss this issue of too much change and what we might do to address it, I’m delighted to have Robert Cole. Robert is Managing Director of the Centre for Change Management. Robert is an experienced coach, consultant and trainer in organisational change and he works extensively with business and government and he is also a valued long-term associate of ours here at pearcemayfield. Robert, welcome and my thanks for coming in.

Robert Cole: Thank you, Adrian. It’s really good to be here.

AB: Robert, let’s get straight down to brass tacks!

RC: It’s a feeling inside an organisation that is a rotten place to be. It feels like being overwhelmed with the demands of the day job and the need to change and you can’t decide which one to do, which is the priority. Typical symptoms that you find when you talk to people in an organisation with too much change is that you get a lot of disengagement and apathy amongst the staff, particularly about when you bring along a new change idea.

Lots of anxiety and stress, burnout and fatigue tend to be things they talk about a lot; there is always automatic resistance to change; you end up with a lack of focus on operations as well and attrition and high staff turnover. People talk about leaving. It’s not a nice place to be.

AB: And this lowers morale in the organisation?

RC: Definitely lowers morale.

AB: OK, so that’s a long list of rather horrendous symptoms I’m sure, many of us would recognise some of those within ourselves and our own organisations. What is the cause of the problem, what are the causes of these problems?

RC: I think the principal cause is senior managers piling on change without thinking about of resources that are needed to commit and deliver a successful change; so they are just not aware of doing this, and some of the assume (quite wrongly) that change can be achieved with any additional resources.

But a lot of organisations today, their organisational capacity has been pared to the bone, they are really trying to get lean and mean and that doesn’t leave much space left for doing the change, on top of the day job and that’s where the pressure on the staff really comes forward. Senior management rollout the change and they just assume that they almost have infinite capacity to do change and it just doesn't work.

We can see that quite simply the demand for change exceeds the available resources – which is the change capacity. That sounds quite simple, but of course in practice understanding people resources in an organisation is quite complex: you have to think about includes skills and capability; it’s not just about bodies.

Because people are being asked to do too much they end up doing a lot of tasks poorly; that means both their tasks for their day job in the business and their task for doing the change; they don’t do either of them very well and then you end up in a vicious circle. That leads to unsuccessful change and benefits not being realised, you also get a lot of disruption to business as usual, both of those lead to the business performing worse than it was before and that means that there are less resources for doing change and the business; and you can see how an organisation like that spirals down.

AB: Yes absolutely, indeed.

AB: This all sounds rather depressing, but of course many companies have broken this cycle. How do they do that – is there a secret? If so, tell us!

RC: Well, there is no magic about it, unfortunately. The challenge is the senior managers have now got to set a hold of the change that’s going on inside their organisation. They have got to realise rampant change doesn’t work. But this is not easy and as these are the managers who have been initiating all of the change, so they have got to take answer to it.

Clearly the answer is fairly simple: you just need to reduce the amount of change to the essential core which has the largest strategic impact that fits within the available capacity in the organisation.

But as I said earlier, determining the capacity of an organisation-there is a little bit of elasticity in there.

There are usually two types of change going on in an organisation: you get internally driven change which is local innovation, try to do things better which is really important for keeping up with the competition and then there is the strategically driven change, driven ideally by pressure of events from outside and try to bring the company into a good place to be ready for the future. Both of those types of change need to be brought under control. And the best practice mechanism for doing that is Portfolio Management. The goal is to reduce the amount of change to fit within the capacity inside a recognised Portfolio.

AB: Balancing the internal and external drivers, because they have to both be addressed. Sorry to interrupt your train of thought but you just mentioned Portfolio Management a while ago. I know that portfolio management is a big topic but can you give us a high level overview of where that sits?

RC: That is a good idea Adrian, I’ll have a go.

But there are a few basic concepts that can be applied:

• Ensure that all the change is aligned to the strategy of the organisation, including incremental change, and that gives you a mechanism for beginning to prioritise the change.

• Then you allocate resources to change initiatives to make sure they will be successful, and that means that once you have allocated all of your resources or most of your resources down the priority list, you reach a point where you can draw a line and say ‘if we go funding change beyond that line, we are overusing our resources and we will end up where we don’t want to be’. So people need to understand and manage the organisation’s change capacity and capability and then use prioritisation using the above constraints. People have to make hard decisions.

AB: There are two issues there: the understanding of it, and then is the management of it with a wrapper of available resources around it and business as usual, so it is quite complex isn’t it?

RC: Yes, it is!

AB: That all sounds very good, but implementing portfolio management clearly is not easy. I’m a just a tad concerned that we may be getting towards ‘let’s blame the managers’ mode here so how can the managers be supported? What advice would you give the managers, and in a way we are all managers within the organisation, what advice would you give them, what tools to help them on that journey, to help them succeed?

RC: My suggestion would be is to look at some recent work that appeared in the management papers. There are a couple of very good ones: the first one was an idea from John Kotter; and what we are trying to do is to sort of see how do we manage those change resources and try to keep them separate from business as usual resources. And John Kotter came up with this idea that there are two types of systems inside an organisation: we have the operational system- does business as usual and normally is managed as a hierarchy in the traditional way and, that’s what we traditionally think of managing a business. But then we have a strategy system, whose job is to steer the strategy of the organisation, decide what changes are necessary to implement the strategy and then make those changes on the operational system. And that is usually organised in a much more fluid network way, because obviously we are changing across the whole organisation and we don’t want to be tied into the structure that we are using to manage our operations, we want to separate them out.

AB: OK, so cannibalising resources from elsewhere is not acceptable really, is not going to give the right result.

RC: No, you really have got to set aside the resources. The people in both organisations are potentially the same, but sometimes people are working in the operational system, and therefore driven by operational priorities, but then we take people out of the operational system, get them to work in the strategy system, and there their priorities are doing the change, so each person knows what their priority is, whether it’s the day job- doing operations or changing operations, and now there can’t be any confusion.

AB: That’s an interesting point, isn’t it? Because you are saying that the change managers, change leadership needs to come from within, because the change manager needs that credibility, I guess?

RB: Yes, change managers do need credibility, so they are normally part of line management but they are given a new priority and other key second structural mechanism that I use is keeping line managers and change managers as two separate groups of people. People, individuals, would move backwards and forwards between the two, because of course if someone is good at line management is probably good at change management, because generally they are good managers.

AB: And good stakeholder engagements.

RC: And good stakeholder engagements skills involved in there as well.

AB: Robert look, we could talk at great length and that sounds, I think for now, a very good place to leave it, so a fascinating and insightful look at change capacity, thank you. I believe you produced some material to support some of the things you have said in this video and fleshed it out a bit more detail. Would you be willing to share this with our viewers?

RC: Yes of course, Adrian. There are some pictures to go along with the video and a small script.

AB: That’s great thanks, and I’ll give you details on how you can access that in just a moment. Let me just try very briefly summarise: I hear you saying that whether or not we find it comfortable we all operate in an environment of change and whether or not we have “change leader “ in our job descriptions, each one of us has a role in delivering successful and lasting change. There are tools to help us on the journey and it is possible to square the circle with business as usual in a V U C A world.

RC: Yes.

AB: So these are all positives, but we all need, organisations need to devote the resources to this task in hand.

RC: That about sums it up, well done Adrian.

AB: Would you go as far as to say that an organisation which commits, fully commits itself to doing change well, we’ll have a distinct commercial competitive edge?

RC: I think it definitely would, because you would end up having successful change and that would lead you to having more resources to do more successful change, so instead of being on a downward spiral, you would be on an upward spiral leading to success.

AB: That’s a great place to leave it - change management, a virtuous circle, I suppose we can summarise.

RC: Yes.

AB: Thank you again, Robert, it has been terrific to see you.

Thank You For Your Enquiry.

Our representative will get in touch with you shortly.You can also:Call Us: +44 1349 470002

Email Us: info@pearcemayfield.com

Thank You For Your Enquiry.

Our representative will get in touch with you shortly.You can also:Call Us: +44 1349 470002

Email Us: info@pearcemayfield.com